Faces of Iraqis: where are they now ?

Their names could be Mary or Robert, Ashley or Joan.

They are painters, teachers and artists. They live in an ancient city, surrounded by desert.

For some time now, they have lived in a heightened sense of awareness; Theirs is a psyche wavering between worry and salvation, of an uncertain future over which they have no control.

''There were constant rumors that the war was coming, either in the next few days, or sometime next week,'' says Troy resident Joe Quandt, who lived among those waiting for the bombs to fall.

''It was very interesting seeing what the mentality was; how the people would go about their day-to-day business. Sometimes they would look at me though, and ask : 'Joe, when is it coming, the war?'

I would say... 'I don't know.'''

Quandt visited Iraq in October, making many new friends during his monthlong visit.

He was especially close to four artists whom he met in Baghdad.

Zienab Aisa is a gallery owner with a raspy laugh. Yusraa Al-Abaddy claims Picasso as one of her biggest influences. There is also an artist named Nazar, and another named Sa'ad.

A painting by Al-Abaddy hangs on the wall of Quandt's house in Troy.

''They all spoke a fair amount of English, and like all the Iraqis, they are a warm,

generous and hospitable people,'' Quandt says.

''These are people who shared their food with me, and told me about their lives. People who asked about America and about what the Americans are thinking,'' Quandt says.

''They are people who care about their children, and for children everywhere.''

Quandt is especially concerned about them these days. He has been unable to contact with them, and has no idea where his Iraqi friends are. He has posted a message online in the hope that they will see it.

''An Open Letter To Baghdad'' from Albany, Quandt's message begins:

''Dear Sa'ad, Zienab, Yusraa and Nazar, I did try to post a letter to you, but it came back. I know you understand about this.''

Quandt doesn't know whether they were able to escape Baghdad, or if they have remained in the city.

''If you have money to be able to leave, you get out. But the vast majority of the people cannot leave the country - and if you are anywhere near any kind of telecommunications area, you

are especially in danger. Once it starts to come, large numbers of refugees will be sent

(fleeing) in all directions.''

He remembers what Nazar told him about what it felt like to be living in Baghdad with war looming on the horizon. ''It's like Iraq was put in a hole,'' she told him. ''It's like we are

watching a movie about the world, and we are not in the movie.''

The whereabouts of Ghazwan Al-Mukhati is a foregone conclusion. When Quandt conducted

an interview for ''CounterPunch'' with Al-Mukhati, the openly vehement denouncer

of Saddam's regime responded: ''I can't leave here, I'm too old.''

He and his wife planned on staying put. '

'We'll stay in our house and wait for the bombs,'' said Al-Mukhati,

a 1967 graduate of Marquette. ''What else can we do?''

Half of Iraq's population is estimated to be 18 years of age or younger, but many

remember the Gulf War in the early 1990s. Quandt met a young man who worked

in Baghdad as a waiter. ''He was talking about the Gulf War and he said he remembers

people crying, buildings falling and people being killed. There are people who were children

at the time. The memory of it is very frightening to them.''

Quandt says he was motivated to learn more about Iraqis and their culture when he

first learned of how children were dying as a result of the United Nations sanctions.

He joined the ''Voices in the Wilderness'' group and traveled to Iraq in October.

''I wanted to go visit with the people, to witness what was going on, to photograph them

and tell their story.'' His journey took him to Karbala, and Najif, but most of his time

was spent in Baghdad.

He says he was impressed by the gentle demeanor of the people and the beauty of

their surroundings.

''The architecture of the buildings is fascinating, the public sculptures, the gardens,

the rows of palm trees. The Tigris River ran right by the window of the hotel

where I was staying, five floors down.''

He also remembers the heavy smog and the stifling heat, which, even in October,

was 107 degrees.

The self-described grandfather/actor/teacher/cab driver/activist has been writing and

talking about his experiences in Iraq since his return in November - sharing stories about

the friends he made, and putting a face on the people who told them.

He also took many snapshots, although this was, at times, a risky proposition.

''They see an American in a public place taking pictures with a camera and they say:

'What's going on here ?''' Quandt recalls.

Communication restrictions can be oppressive, as well.

''There is television, and you would watch a few musical acts, but mostly TV is all Saddam,

all the time,'' he says. ''And the Internet is completely controlled. There are one or two (browsers) and they are heavily monitored. You can send e-mail, but you can't say anything negative.''

Government monitoring aside, there is a strong presence of and appreciation for art,

with 45 galleries in Baghdad, Quandt says. As far as a normal routine, he says the people

work six days a week, with Friday being ''Mosque Day,'' a day off from work.

''Iraqis are very proud of their culture - their writing and music, their art and astrology,'' Quandt says. ''It is the Garden of Eden and it is the Tower of Babel. This is Iraq.''

It is also a region in conflict. ''They are aware of what is coming,'' Quandt says. In preparation for the war, he says, people were digging holes and trenches in their back yards and filling them with sandbags.

''They really don't know what to expect,'' Quandt says. ''And the type of weapons

that they will be subjected to, nobody knows. I only wish that Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney

had friends there.''

As far as gauging the thoughts of the people he met in Iraq, Quandt replies, emphatically:

''They don't want Mr. Saddam.'' But he also responds just as emphatically that the citizens of Baghdad don't want to be attacked - that having their city totally destroyed is not a viable option, either.

And so it was on Thursday, at 5:30 a.m. Iraqi time, that the first signs came that everything was about to change.

By Friday, rumors were plentiful: The Iraqi military had built trenches and filled them with flammable oil throughout the streets of Baghdad; Saddam Hussein was taken out early, in an orchestrated strike by the U.S.; the Iraqi military was negotiating their surrender.

The world tuned to its televisions, where cameras sat on tripods pointed at Baghdad

waiting to capture the visuals of something that was called the ''Shock and Awe Campaign,'' bringing it live, in real time, into homes around the world.

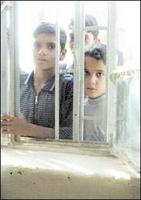

by Thomas Dimopoulos originally published in The Saratogian, March 22, 2003 (photograph of three young boys in Iraq, before the bombings, by Joe Quandt)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home