Tang Goes POP: Andy Warhol remembered

Andy Warhol died Feb. 22, 1987

By the time Andy Warhol began messing around with silk-screened Marilyns, Elvises and Liz Taylors, bop and free jazz, and the beat-inflected prose of Kerouac, had already effectively killed the complacent '50s.

Coffeehouse poets ditched their black berets and strapped on guitars, and the very young were seduced with the emerging imagery of so-called ''pop'' artists.

In 1962, the future was being ushered in on a multi-colored rainbow and, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, the period was encrypted with a series of time-triggered flashes that jarred an oblivious nation and redefined its vocabulary to include extra emphasis on words like acid, assassination, The Beatles and napalm.

In the visual arts, Robert Rauschenberg pasted together sheets of paper and drove nails into a flat paint-dripping surface and called it art. His collaborations - like those with choreographer Merce Cunningham, and with composer John Cage - were with artists working in different media.

Rauschenberg's friend Jasper Johns was already a featured artist, showing in solo exhibitions - nearly a decade had passed since he started painting his famous flags, and all the buzz was about artists like Oldenberg and Wesselmann, Warhol and Lichtenstein.

Popular culture, by way of definition, both reflects and invents society. In the mid-1960s, when musician Lou Reed sang ''I'll be your mirror, reflect what you are, in case you don't know,'' - in Andy Warhol's Factory, no less - he nailed the meaning of ''Pop Art'' head-on.

To survive, art needs someone to love it, cherish it, and show it off.

For more than 40 years, Ileana Sonnabend has been doing all of the above. A collection of her life's labors have come to the Tang Museum and Art Gallery.

''From Pop to Now: Selections from the Sonnabend Collection,'' is an exhibition of works from the private collection of gallery owners Ileana and her late husband Michael. After Ileana's marriage to art dealer Leo Castelli ended in 1959, Ileana married Michael Sonnabend in 1960. That year, the couple opened their first gallery.

Fifty-four different artists and 81 works are part of the Tang exhibition, according to the museum's Director Charles Stainback.

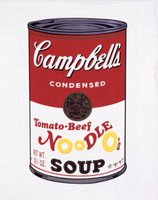

Among the works anticipated to appear are Warhol's 1965 silk-screened acrylic Liz Taylor, soup cans and Brillo boxes, as well as works by Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenberg, Roy Lichtenstein and Jasper Johns.

Anselm Kiefer's photography of the 1960s and '70s illustrates his attempt to understand and process the Nazi machine of World War II. Kiefer was born in Germany in the waning weeks of the war that would eventually frame much of his work. His contribution to the Tang's exhibit is the 1978 ''Baum Mit Palette.''

Artists that mix animate and inanimate sculpture, like Jannis Kounellis and poet-turned-performance artist Vito Acconci, will be shown as well.

Acconci originally performed one of his earliest - and most notorious - works at the Sonnabend Gallery in 1971.

And 1960s London art students Gilbert and George, who blurred the lines of art and life when they - in well-groomed, well-dressed and self-painted fashion, actually ''became'' the art - will be represented with their 1986 work, ''They.''

The exhibit covers a period beginning from the mid-20th century to more recent work, such as Rona Pondick's eerie looking ''Dog,'' from 2000.

Travels with Charlie

For the Tang, ''Pop'' is a major showing.

Charlie Stainback originally had associations with the Sonnabend gallery in the 1980s. The current exhibit was two years in the making, he said.

Prior to the opening, I had the opportunity to play the proverbial fly-on-the-wall. In the interest of behind the scenes snooping, I thought it would be neat to share.

June 18, 2002: Just a few days earlier, the rooms were vacant and the walls a white-washed void.

At this hour, however, the floor space is growing increasingly crowded. Corrugated boxes, neon crates, and construction materials of all shapes, sizes and design are everywhere. Further complicating matters is a seemingly endless stream of incoming deliveries, postmarked from every corner of the Earth.

In just a few short days the Tang was to host its opening gala for its grand exhibit of the season, ''From Pop to Now: Selections from the Sonnabend.'' With less than 72 hours to go before the display opened for the big opening, there were still paintings to be hung, exhibitions to be displayed and installations to be, well, installed.

The calm in the middle of this firestorm of activity stood a man whom everyone addresses simply as ''Charlie.'' Charlie is Charles A. Stainback, director of the Tang Museum.

As the exhibition took shape, he was also the director of all the human activity going on inside the space, as well as the envy of art gallery directors the world over.

''My museum colleagues are amazed,'' he said, one arm hugging an iron pole leading skyward in the Tang's gallery.

Higher still, perched on platforms, artists were constructing a full, wall-length Sol LeWitt piece from a sheet of instructions.

The amazement stems from Stainback securing the American premier of the exhibit for the Tang.

With obvious options like New York City or Los Angeles or Chicago, that the collection has landed in Saratoga Springs first is a significant achievement.

Stainback, whose first love is photography, has had an ongoing relationship with the Sonnabends since the 1980s. This particular exhibition was years in the making.

''Most museums plan three to four years out,'' he said. ''Here, we're about two years out, and we have the ability to be totally flexible.''

Niceties aside, we were simultaneously captivated by one particular crate. From its exterior markings it is apparent that the content of the purple, rectangle-shaped monster is a Warhol. Instantaneously, and out of thin air it seems, two men emerged to begin unraveling the layers of packing material. Finally, the dramatic moment came, and the piece was revealed.

The men paused to put on white gloves - the type you usually see reserved for royalty - then proceeded to carefully lift the piece.

When the light hit the multi-colored work - a turquoise 1963 piece depicting ''Liz'' Taylor - each fabric of the its brightness reflected a different, and increasingly illuminating layer of the past 40 years of American culture. It was a mind-boggling moment, and it seemed the sound of trumpets should have been heard somewhere.

June 21, 2002: A few nights later, the opening took place with much fanfare. The entryways were marked with big silver five-point balloons and a band fills the room with a jazz melody.

Somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 invited guests mingled to watch video artists communicate on big screens, inspected Rauschenberg's torn canvas splashes, and Claes Oldenberg's humongous muslin-in-plaster soaked ice cream cone.

An entire area of the exhibit is reserved for Warhol - Campbell's soup cans, Kellogg's corn flakes, cases of Del Monte peach halves, and red, white and blue Brillo boxes.

All the while, artist Roy Lichtenstein's creation - a dark-haired acrylic seductress - stared back with her flirtatious, over-the-bare-shoulder eyes that followed you everywhere.

Ileana Sonnabend, whose collection it is, and Oscar Tang (for whose late wife the museum is named) mingled with guests and a number of artists who attended.

Jeff Koons posed next to his silver-colored, stainless steel ''Rabbit,'' as Yaddo President Elaina Richardson took in the vastness of it all.

''It's something to come back to see, four or five times, at least'' Richardson said of the visual feast.

There are 81 pieces in all. And the first thing you realize is that many of these are real things - every day things - functioning as art.

Then there are the things that appear to be real - but actually, aren't real at all. Most of all, I suppose it is the things that really ARE real things that are the most unbelievable of all. Or, as one of the display pieces upstairs reads: ''Making reality look more real than it is.''

by Thomas Dimopoulos The Saratogian, June, 2002.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home